This article first appeared in Anach Cuain 2003.

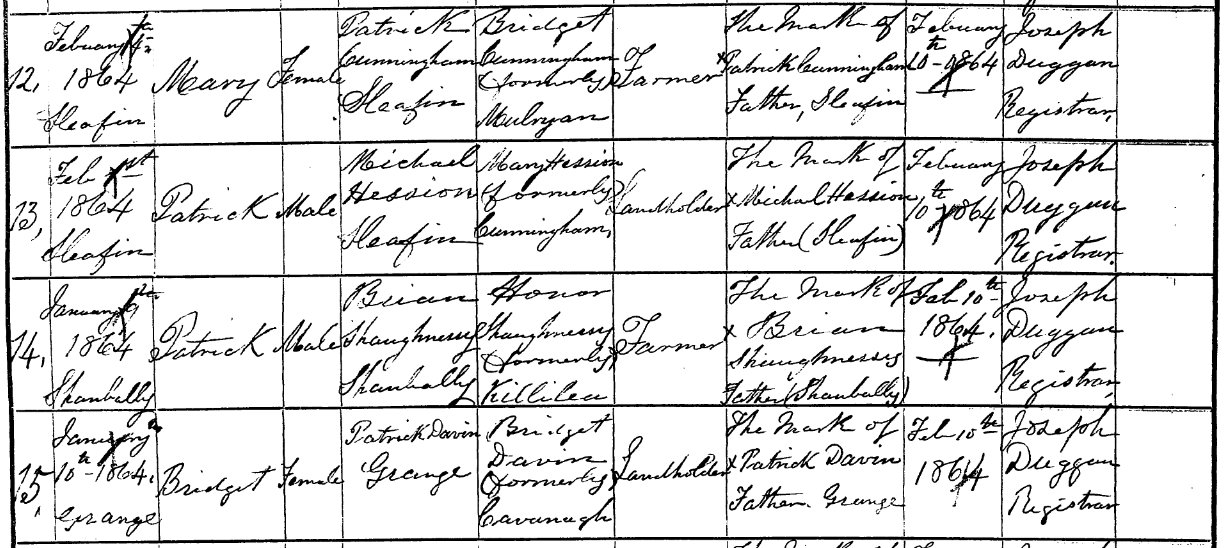

One of the intriguing questions that families grapple with today is tracing their “roots” – who their ancestors were and where and how they lived. In such cases they rely on folklore passed down from one generation to the next or try family history societies who compile data on such matters. Searchers are directed to try “Griffith’s Valuation”, the national census of 1901/1911, Tithe Applotment books; Baptismal/marriage/death registers, old headstones, shipping lists of those who emigrated and last but not least the Mormon database in Utah! Despite all these references, it is difficult to trace family links back for more than two or three centuries. Was Annaghdown parish populated during the time of Brian Boru and if so did the inhabitants ever hear of the great king? Well we know that St Brendan and St Briga with their communities lived in Annaghdown long before the times of Brian the brave. Dare we enquire how far back in time we can go regarding human habitation in this parish?

Yes, we have some evidence gleaned from within our own district! We hit the jackpot way back in 1934 though few people knew about the discovery then, and perhaps not many know about it today. Remain in ignorance no longer for this is how it happened. At that time the local farmers were forced to try a variety of means available to them to eke out a living on their small holdings of land – not only by raising stock but by such enterprises as cultivating sugar beet or by selling turf, cabbages or potatoes. During the month of November 1934 potatoes were selling at 4d. per stone, butter at 1 shilling a lb., eggs at 2s. 6d. a score, hay at 25 shillings a cwt. while two year old heifers and bullocks would realise 46 each. An editorial in the Connacht Tribune at the culmination of the year complained scathingly of the woes that beset agriculture stating that there was “an intensification, if anything, of the sublimated futility of the economic war and the slow but sure destruction of the Irish livestock trade which it took over a century to build tip.”

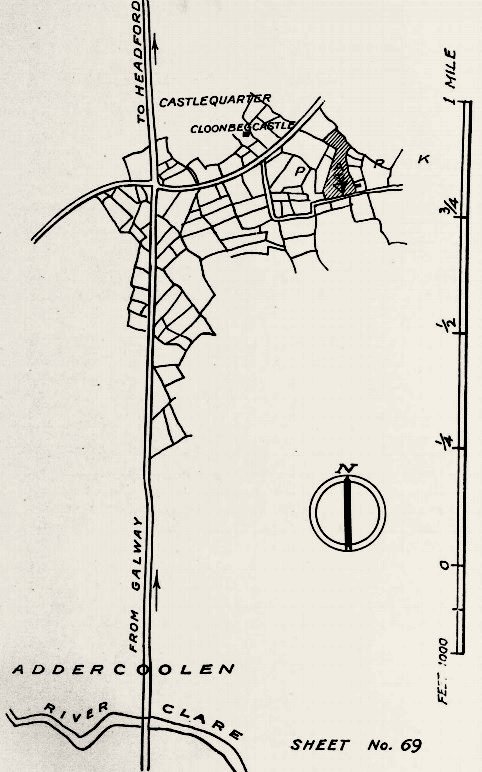

A small but significant economic venture at the time in the townland of Park was the digging, by pick and hand-shovel of lorry loads of gravel for sale in Galway city or the hinterland. During the month of November 1934 Edward McNamara together with his son Patrick, (now over eighty years of age) and their neighbour John Hannon were working on the site. Working down through the gravel pit was laborious work, which Patrick then as an eighteen-year-old can still recall. As they dug through the pit, they piled the finer sand on one side which was sold by lorry load for £3 to Patrick Dooley, Liscannanaun and transported to Galway. On this particular day they had barely lifted off the covering layer of clay and some fine gravel to a depth 12 inches when they came upon a large flat stone 3 feet 11 inches in length by 2 feet 8 inches in width. Underneath this top stone covering they were amazed to see some bones like human remains. Though they did not know it immediately, they had come upon a most important discovery of an ancient grave or cist burial. Luckily the matter was reported to the Gardai who in turn had it investigated without delay by Professor S. Shea, UCG. In an article written in the Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, the professor describes the location as situated on top of a natural hillock, just inside the wall bounding a side road and about three quarters of a mile east of the Galway-Headford main road.

The contents of the cist, according to the examiner, had been interfered with, presumably by children on the neighbourhood, as several of the bones including the skull were obviously displaced. When the contents of the grave were examined in detail, it was found to contain some small pieces of reddish burned clay like charcoal near the feet of the skeleton suggesting broken fragments of an urn. It was customary to place such a vessel of food in the grave with the deceased person to carry on the journey into the next life. The skeleton, dating back to pre-Christian times, was found in a tightly crouched position, practically complete and in an excellent state of preservation. It was ascertained that the remains was that of a broad-headed, broad shouldered, strongly built man, of about 5 feet 8 inches in height and something of over forty years of age. Following the investigation by Professor Shea the skeleton, known as the “Park skeleton”, was taken to Galway where it was placed among the anthropological collection at UCG. Today such a find would surely attract great attention from the media but in 1934 there wasn’t even a mention of this discovery on the local papers.

Indeed only three items of interest regarding Annaghdown parish appear during the months of November and December, none dealing with the archaeological find. One news item of local interest concerned representations made by the parish priest Rev. E. McGough to the Minister for Industry and Commerce, Sean Lemass, who decided to send an inspector of the Geological section of his department to Annaghdown to enquire into and report on the possibilities of reviving the brick industry in the district. The inspector was to be on the scene without delay. (It should be noted that there was an intense campaign on foot in Galway for the forthcoming general election at that time.) Two further items of interest concerned religious affairs in the parish: that Fr. John Fitzgerald, Annaghdown was transferred to Tuam as curate and a short note in the same newspaper mentioned that Margaret Hanley, the eldest daughter of Michael and Ellen Hanley, Slievefinn was professed as a Religious Sister in Minnesota, USA on November 21st.

Though the Park discovery did not reach the newspapers of the day, it is of great significance for us today. The fact that the find can be dated back to the Bronze Age, (2000 BC- 500 BC) illustrates how this parish was inhabited by people long before the time of Christ. This was a time of great technological progress with the widespread use of copper, bronze and gold for tools and ornaments; of deforestation and of more widespread travel on land by built pathways or on water by boat. Were there pathways criss-crossing through the Curraghrnore bog? We can only surmise what use the inhabitants made of the local waterways of Cregg, Clare and Corrib. The answers remain in the realm of conjecture.

Our deepest admiration and gratitude goes to Patrick McNamara, his father Edward and neighbour John Hannon, Park for leaving the cist intact for professional investigation. Due to their care, we now have tangible evidence of human habitation in this district almost four thousand years ago – that’s how far back we can go, at least until someone else makes another find. Keep digging.